Bring Back The Crack in the Teacup

There's a very interesting conversation happening on twitter right now about Joan Bodger and the fact that her brilliant and devastating memoir The Crack in the Teacup is currently out of print. If you'd like to chime in on this discussion you can find me @saraoleary over on twitter. And if you feel inclined I'm looking for people to support a plea for bringing the book back into print.

There's a very interesting conversation happening on twitter right now about Joan Bodger and the fact that her brilliant and devastating memoir The Crack in the Teacup is currently out of print. If you'd like to chime in on this discussion you can find me @saraoleary over on twitter. And if you feel inclined I'm looking for people to support a plea for bringing the book back into print.Meanwhile, I dug out the review I wrote when the book was first published and here it is.

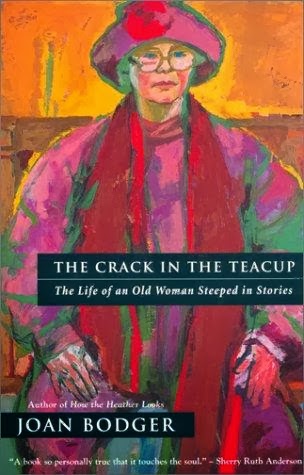

There is real life and there is storybook life, and I never expected the twain to meet. But in the person and works of Joan Bodger, they do. Joan Bodger, author, storyteller and gestalt therapist, has spent her life reading and telling stories, and the result is her new autobiography The Crack in the Teacup: The Life of an Old Woman Steeped in Stories (McClelland & Stewart, 412 pp., $34.99).

Bodger's name was already familiar to many readers because of her wonderful tale of a family's very personal quest, How the Heather Looks: A Joyous Journey to the British Sources of Children's Books (McClelland & Stewart, 249 pp., $29.99). To read the two books in tandem is to risk laying the heart bare to all the joys and sorrows of both childhood and parenting.

How the Heather Looks was first published in 1965. It was out of print for more than 30 years before it was brought out in a new edition. In the meantime, copies were passed hand-to-hand, illegally photocopied, borrowed and never returned. It had the dubious honour of being the book most often "retired" along with retiring children's librarians.

It tells of how, in 1958, Joan and her husband John took their children Ian (almost nine) and Lucy (two-and-a-half) on a trip to England. The couple had come into what Bodger calls "a modest windfall" and decided the children should have the opportunity to see the places of storybooks such as A Child's Garden of Verses, The Wind in the Willows, Swallows and Amazons, and Puck of Pook's Hill, among others.

It's a glorious idea, and halfway through reading the book I was ready to call the travel agent and book passage on a Cunard liner, modest windfall or no.

Their trip is lovingly described, an idyllic journey where the storybook characters resonate with meaning for the four family members. Ian, at nine, is curious and fearless, disappearing down country roads, scrambling over bluffs, shadow-jousting on the ramparts of castles. He is Puck, and King Arthur, and the boy narrator of Robert Louis Stevenson's verses all at once. Lucy, at two, dressed in practical corduroy overalls when all little English girls of the time wore little nylon dresses, red-haired and lovely, running down paths ahead of her parents, looking for Mrs. Tiggy- Winkle.

It is all achingly perfect and perfectly real at the same moment. And then, in Bodger's new afterword to the book, we read how, before the book was even published, the family had suffered the devastation of death and schizophrenia.

Wanting desperately to believe in the idyllic world where parents and children can travel into pages from storybooks brought to life, I almost had to make myself open The Crack in the Teacup,Bodger's autobiography. Can't I just leave them all on holiday? I wondered. Ian and Lucy forever children, Joan and John forever happily married.

Reading the autobiography was a completely different experience. Not that it wasn't an enjoyable read, because it was. Bodger writes of the events of her American childhood, how she was moved to join the army, her courtship and marriage and the birth of her children. It's all very interesting but not particularly extraordinary.

Now 77 and suffering from exhaustion and illness in the aftermath of completing her memoir, she shows that a life can equal much more than the sum of its parts. What lifts her book above the ordinary run of recollections is the relationship she has to myth and story. In the period when she was writing How the Heather Looks, her young daughter developed a brain tumor and her husband began showing symptoms of what would later be diagnosed as schizophrenia. He was institutionalized as a result of hallucinations and she was left alone with two small children.

Her brother-in-law refused her an advance from the family trust to enable her to attend library school because he said he'd noticed that in cases where the wife went to work, the marriage generally ended in divorce.

She was heartened to learn that one of the other mothers from her daughter's class, Betty Friedan, was also writing a book. She called her up, but Friedan said she was too busy to talk to every suburban housewife who called her. Still, Bodger wrote her joyous book about a "joyous journey." It strikes me as a remarkable achievement.

Bodger came through the devastation of her family and began again. She worked at nursery schools for the poor and in education and library studies. She reviewed children's books for the New York Times and became an editor in the children's division of Random House-Pantheon-Knopf.

She married a Canadian, moved to Toronto, trained as a gestalt therapist, started a storytelling group and became a tour leader for literary trips to England.

Bodger's genius lies in shaping her life into narrative. She writes: "There is a genre of fairy tale in which the hero or heroine must go through a door, or run through a forest, or face a dragon, or jump down a hole, not knowing the outcome." Sounds a lot like life.

The Crack in The Teacup is a brave book, free of self-pity or recrimination. It is one to learn from.

(article originally published Vancouver Sun, December 9, 2000)

Comments